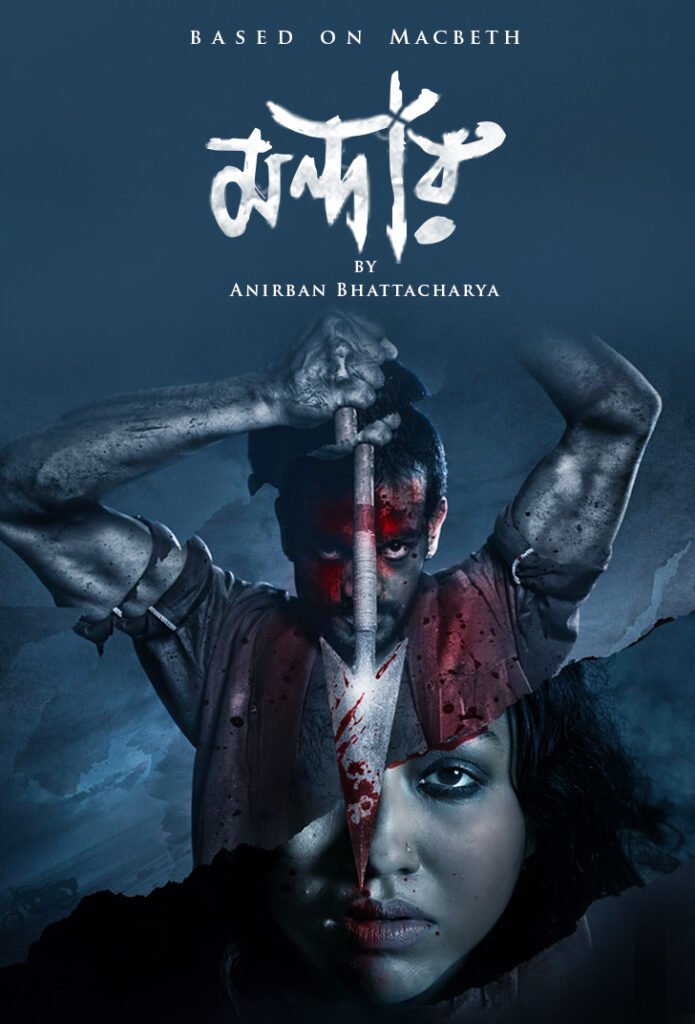

Mandar, a realistic version of Macbeth has released in Hoichoi. Is it worth watching? Here is the reveiw.

If Shakespeare’s works lend themselves to adaptation, Macbeth is tailor-made for retellings. The universality of its ideas – power’s lure, its resultant corruption, and the harm it does – has long trumped the play’s details. The text’s power dynamics have been applied to a variety of scenarios. Akira Kurosawa famously remade it in mediaeval Japan in Throne of Blood (1957), and Vishal Bhardwaj rooted it in the Mumbai underworld trenches with Maqbool (2004). Dileesh Pothan rebuilt the skeleton of the tale in a household setting more recently in Joji (2021), linking feverish ambition for the throne with the ingrained craziness in a patriarchal setup. The idea of a loyal sentry who becomes insane after plotting murder is so permeable that it may be used to investigate darkness in both the land and the heart. It’s no surprise, then, that Tollywood’s blue-eyed boy, Anirban Bhattacharya, chooses this path for his directorial debut.

Mandaar, a realistic version of Macbeth, arrives just in time for Hoichoi. Since its launch in 2017, the streaming behemoth has gone to such pains to host a specific type of movies and television that it has become a genre in and of itself. The shows are infected with the aesthetics of soft porn, reducing sex to both the plot and the narrative point, as any dedicated user of the service will attest. The streaming service needed a makeover as rival platforms made inroads in innovative storytelling. And there was evidence of the effort all everywhere.

Mandar begins with a prophecy. A spirit-like woman foretells the future of the local goons when Mandaar and Bonka return from carrying out their leader’s orders. One will become a king, while the other will produce kings. The throne, however, is already taken by Dablu bhai, a promiscuous middle-aged criminal, in Gailpur’s coastal district, where people’s livelihoods are reliant on fishing and their lives are as insecure as their prisoners’.

The pleasure of seeing a rewriting is in being astonished, despite the familiarity, by how closely it follows the source material and how far it may still go. The five-part series, written by Pratik Dutta and Anirban, is so loyal to its original material that the play relies significantly on the screenplay, contriving it rather than guiding it. It’s also because of this that playful creativity like Laili (Mandaar’s wife) being Dablu’s mistress, which effectively subverts Lady Macbeth and Duncan’s chaste connection, never sings. This rigidity had the most impact on Laili’s (Sohini Sarkar’s) portrayal, stripping her of the much-needed nuance that a figure like her required. Then there’s the first-time director syndrome, which means there are a lot of thick metaphors, weird camera angles (one is under a character’s armpit), and esoteric animal symbolism throughout the series.

Mandaar is still worth watching even after that. Macbeth’s liminal state before to his awakening has been shown in a variety of ways over the years. By recognising power as a manifestation of gender, Anirban exemplifies this point. His Macbeth is more emasculated than any of his contemporaries, and it is this’redressal’ that explains his ugliness. It’s a moving suggestion, complete with its own commentary on hypermasculinity’s dangers.

But it’s the show’s depiction of a world that appears eerily familiar that really stands out. Outside of the metropolitan environment, stories are prone to stereotypes. With Birohi, a six-part series posted on YouTube earlier this year, Pradipta Bhattacharyya deconstructed it by refusing to romanticise rural Bengal. Anirban does the same by giving the characters a unique dimension, which is mirrored in production designer Subrata Barik’s attention to detail (Badla, Kahaani 2). For example, a gangster’s residence has a life-sized picture of Amit Kumar, who is known for singing love ballads when inebriated, while a young girl’s room has enormous newspaper cutouts of an actor’s face plastered all over it. These elements, which express the mood and aspirations of the people inside the frame, give the piece a lived-in feel, complementing rather than colouring our reading.

The diversity of a fantastic ensemble is a big part of what makes watching Mandaar so enjoyable. Anirban, a veteran of Bengali theatre, triumphantly blends well-known and lesser-known characters while saving a morally reprehensible role for himself. Debasish Mondal (Mandaar), Diganta (Moncha), and veteran Debesh Roy Chowdhury have all delivered outstanding performances (Dablu Bhai). For a long time, domestic OTT platforms have democratised the star structure by turning new faces into stars, boasting of massive talent beyond the big screens. Hoichoi has accomplished the opposite by not only displaying all that is wrong with the Bengali cinema industry, but also by standing as living proof of its perpetuation.