Kadambini Devi is India’s first lady doctor who fought against all the barriers of stereotypes and patriarchy of India. Here is the incredibly inspiring story of Kadambini Devi that will encourage all the students today.

Women’s rights and education appeared a long way off during the East India Company’s control in India. Women hid behind their veils, while social ills such as child marriage and sati plagued the community.

Most women were barred from obtaining an education or working as professionals. Marriage, pregnancy, and child rearing were thought to be their only options.

This isn’t, however, a story about oppression. Instead, it’s a coming-of-age story about pre-partition India’s first female emancipations. The story of how one woman broke the glass ceiling, defied prejudices, and became a trailblazer for future generations.

This is the narrative of Kadambini Ganguly, one of the first female graduates from India and the British Empire, who went on to become one of the first female physicians in South Asia to be trained in western medicine.

Kadambini Bose was born in Bhagalpur and raised in Changi, Barisal (now in Bangladesh).

Her father, Braja Kishore Basu, was a well-known Brahmo Samaj leader, and her youth was heavily affected by the Bengal Renaissance. He was committed to female emancipation as a headmaster, co-founding the Bhagalpur Mahila Samiti, India’s first women’s organisation, in 1863.

Kadambini received her official education at Banga Mahila Vidyalaya, which eventually became the Bethune School. She was the first Bethune School candidate to take the University of Calcutta entrance exam, and she made history by becoming the first woman to pass the exam in 1878.

In 1883, Bethune College added First Arts (FA) and Graduation courses as a result of her achievement. Together with Chandramukhi Basu, Kadambini was one of the British Raj’s first two graduates.

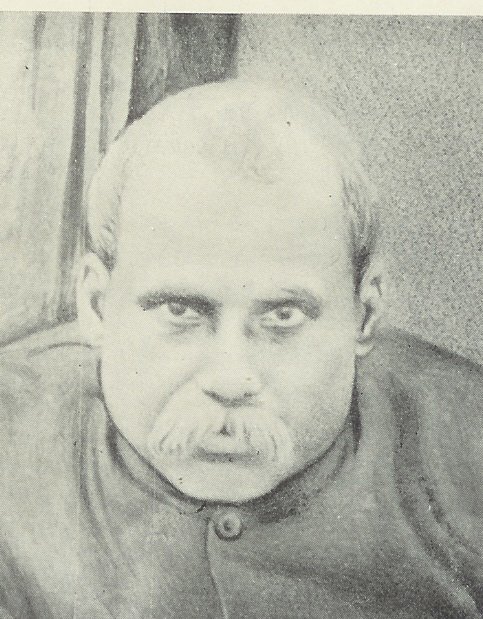

She opposed what the culture thought acceptable at every turn, save from schooling. She married her instructor, Dwarakanath Ganguly, who was 20 years her senior and a famous Brahmo Samaj leader from the Banga Mahila Vidyalaya.

There was no one from Bramho who accepted their wedding invitation.

When most people assumed she would stop studying after graduation, Dwarkanath urged her to pursue a career in medicine. The Bhadralok (upper caste Bengali) group reacted angrily to her decision to do so as a woman.

So much so that Maheschandra Pal, the editor of the prominent periodical Bangabasi, referred to her as a courtesan in his article.

Angered by the editor’s antics, Dwarakanath confronted him and forced him to swallow the piece of paper on which the comment was printed in a not-so-subtle manner. He was condemned to six months in prison and ordered to pay a fine of Rs. 100.

Social Movements

Her ideas were outlandish. She was a driving force behind a number of social movements. She was a key figure in the battle to improve the working conditions of female coal miners in Eastern India. In the 5th session of the Indian National Congress, she was also a member of the first ever female delegation (women who were chosen to vote).

When Bengal was partitioned in 1906, Kadambini established the Calcutta Women’s Conference for unity and served as its president in 1908. She openly supported the Satyagraha in the same year, mobilising people to raise donations for the workers.

She was the President of the Transvaal Indian Association, which was founded after Mahatma Gandhi was imprisoned in South Africa, and she fought relentlessly on behalf of Indians in that country.

At the Medical Conference of 1915, Kadambini spoke out against the practise of the Calcutta Medical College not admitting female candidates.

Her enlightening presentation prompted the university to change its policy and welcome all female students.

After her husband died in 1898, she withdrew from public life and her health suffered as a result. She travelled to Bihar and Orissa a year before her death to assist female mineworkers.

She did not refuse any medical calls until the day she died. She died fifteen minutes after returning from one of her routine medical calls on October 7, 1923. Unfortunately, she died before medical assistance could reach her.

Kadambini Ganguly may be no longer with us as an advocate of women’s education and rights, but she will never be forgotten!

Read more articles at – https://www.unveil.press/prostitution-and-the-life-of-prostitutes/